A gallery within a larger exhibit at the Whitney Museum in New York two years ago has lingered in our minds ever since we saw it. It was entitled Portraits Without People, and we found it provocative. And profound. Because it raised an intriguing question: if someone wanted to capture your essential essence without showing any part of you, what would they paint (or photograph)? The books on your nightstand? Your running shoes? Your last Power Point presentation? What you ate this morning? Said another way: do our possessions define us? Are we what we buy? And if not, then what objects in our lives represent who we really are?

is it possible to paint portraits without people?

The mission of the Whitney exhibition we saw was multi-layered. On the surface, it was an inquiry into a simple question: “Is likeness essential to portraiture?”

Gathering a group of portraits painted by American artists over a span of 100 years, the curator filled a gallery with works meant to explore “alternate means for capturing an individual’s personality, values and experiences.”

In other words, how do you portray someone without actually using their likeness? With no reference to their gender, race, sexuality or economic circumstances? How do you capture their spirit using only objects that can be rendered in a work on paper?

how to portray people without relying on their likenesses

American modernists devised intriguing and clever means for communicating volumes about their subjects without ever creating a figurative representation that would clue the viewer in to any of those demographic boxes.

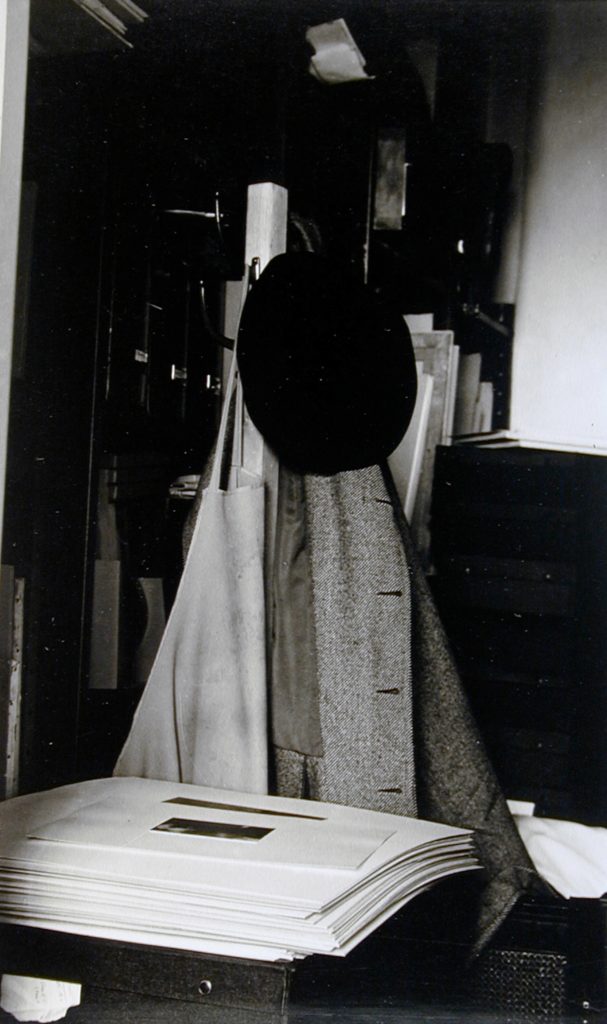

For example, the photographer Dorothy Norman evoked the personality of Alfred Stieglitz, her lover, in a shot of his hat and coat.

Dorothy Norman, An American Place – Alfred Stieglitz’s Hat and Coat in Stieglitz’s Vault, ca. 1940s

A Robert Rauschenberg collage served as a portrait of lives tragically lost, conveyed through layers of deteriorated newspaper clippings, photographs and fabrics.

Here are three others that caught our eye that day.

Marsden Hartley

Take Marsden Hartley, for example, in Painting, Number 5 (1914-15). The Whitney curator notes report that Hartley spent time in Berlin before the First World War. He fell in love with a young cavalry officer, Karl von Freyburg. The freedom and optimism that he experienced in the heady time in Berlin before the war began – where he was part of a community of gay men, despite the legal restrictions on homosexuality – were cruelly shattered when von Freyburg was killed early in the war.

The painting Hartley created to memorialize his lover includes motifs from German flags, a chessboard as a homage to von Freyburg’s favorite game, the Iron Cross he was awarded for bravery, and regalia from his uniform.

Marsden Hartley, Painting, Number 5, 1914-15

A cursory glance at this painting would leave many observers feeling energy, strength, and vitality. You can almost hear the martial music playing. Yet the message behind it is one of loss and heartbreak. You would never know that, though, given its vibrant colors and strong lines. Which made us wonder: did Hartley master his grief in order to portray his lover as he remembered him in life? Young, virile, cerebral, patriotic. We’d like to believe that perhaps that’s how a 20-something year old von Freyburg might have wanted to be remembered.

Jasper Johns

One could even create a self-portrait this way. In his work Racing Thoughts, 1983, the curator notes report that Jasper Johns was sitting in his bathtub one day when a series of images ran through his head “without any connectedness that I could see.“ The resulting work contains both the elements of the actual scene, and the subjects of his thoughts. Which turned out to be connected after all.

Jasper Johns, Racing Thoughts, 1983

Johns includes allusions to his khaki pants hanging on a hook on the wall and the running faucet in his tub to register the actual surroundings that launched this “portrait.”

But then he adds several elements that tie his disparate thoughts that day together. A puzzle portrait of his art dealer, Leo Castelli. A lithograph by Barnett Newman. A reproduction of the Mona Lisa. A pot by ceramicist George Ohr. He mounts them all with prosaic items like tape, thumbtacks and a nail.

It turns out that collectively, they’re a portrait of the art history and personal relationships that formed who Johns is as an artist. In that way, they conjure an image of the artist himself – a self-portrait. Perhaps as he sees himself. Perhaps as he’d like to be seen.

Florine Settheimer

Another artist creates a self-portrait in a different manner and style. Florine Settheimer frequently painted portraits of herself, her mother and sisters, and the artists who visited the family’s apartment in Manhattan. Even in representative works, she always included emblems of the subject’s identify. Clues to their character.

Florine Settheimer, Sun, 1931

In her painting Sun, 1931, the center of the portrait is a bouquet. Each year for her birthday, the artist collected seasonal flowers and recorded the act in her journal. This painting represents her 60th birthday. The ribbon on the vase bears her name, and the bouquet is a stand-in for Florine herself.

How incredible and lovely to think that this is how the artist saw herself at age 60. As a beautiful bouquet of fresh flowers, full of life and color and vitality. Striking to behold. And the center of attention. Not a single shrinking violet among the blooms. We hope we feel that way when we’re 60. We’d actually love to feel that way now.

what objects truly define us?

Which brings us ’round to the original question we’ve been pondering ever since we saw this exhibit. If someone painted your true essence – your character, values, and life experiences, what would they paint?

If you were creating a self-portrait but could show nothing figurative, what would you paint?

Now, go out and live the life that you’d want to see on canvas. Whether or not it ends up in a museum, you and your actions and your possessions are all painting a portrait of you as a person. No time like the present to be sure you’re happy with the end result.

see luxury in a new light

Come and join our community! For a weekly round-up of insider ideas and information on the world of luxury, sign up for our Dandelion Chandelier Sunday Read here. And see luxury in a new light.

ready to power up?

And for a weekly dose of career insights and ideas, sign up for our newsletter, Power Up, here.