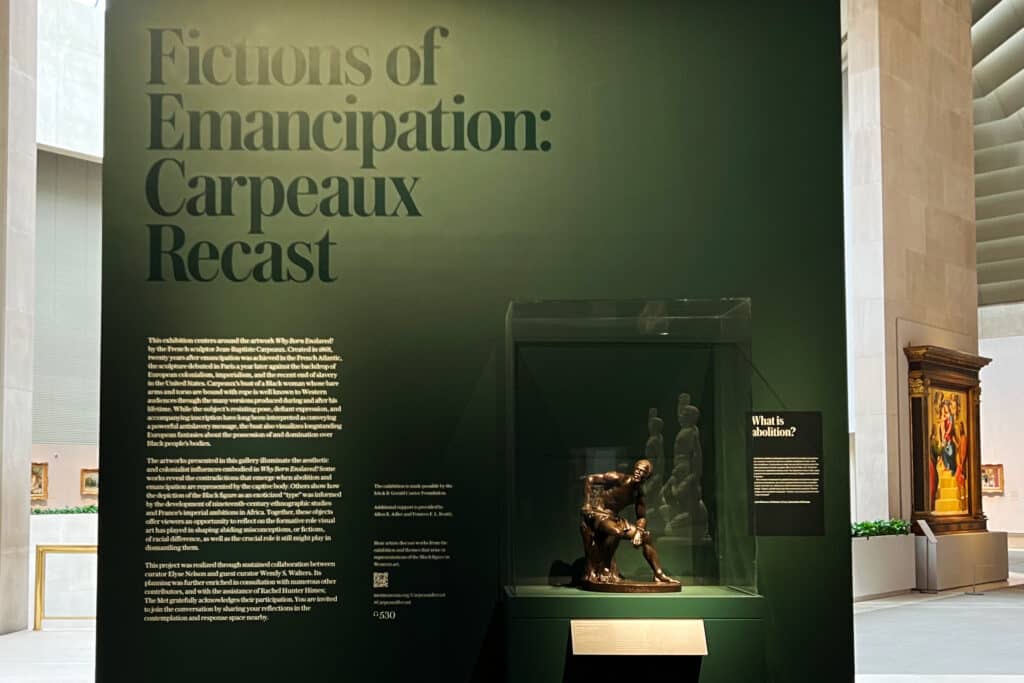

At Fictions of Emancipation: Carpeaux Recast at the Met, a famous sculpture is used as the starting point for an exhibit focused on the fantasies of Western artists about slavery and freedom. For anyone earnestly seeking to understand how slavery, emancipation and the inner lives of the Black Diaspora have been portrayed in Western art, this is a must-see exhibit. And in case you can’t get there, we’re sharing our photos and thoughts from a recent visit.

Emancipation Fantasies Exposed at Met Using One Famous Sculpture

Fictions of Emancipation: Carpeaux Recast is an illuminating, infuriating and ultimately energizing exhibit currently on view at the Metropolitan Museum in New York.

It’s the first exhibition at the museum ever to examine Western sculpture in relation to the histories of transatlantic slavery and colonialism. More than 35 works are displayed, telling the story of Western artists, slavery and emancipation through the lens of one famous French sculpture.

At Fictions of Emancipation: Carpeaux Recast at the Met, a famous sculpture exposes Western artists on slavery and freedom. Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier.

the famous sculpture why born enslaved!

The exhibition has at its center a marble bust of a Black woman. Her bare arms and torso are bound with ropes. Her clothing is torn. Yet somehow her expression seems to convey defiance. To modern eyes, at least, her mien seems resolute and strong.

At the base of the sculpture in French are the words “Why Born Enslaved!”

Carpeaux Recast at the Met Museum. Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier.

Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux, Negresse, 1868

Created by the French Sculptor Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux in 1868, this seminal work was first exhibited with the title Negresse. At the time, this was a pejorative term (not unlike the n-word today).

The sculpture made its debut 20 years after the French decreed the emancipation of Black slaves in their Caribbean colonies. The end of slavery in the United States was, of course, not such a distant memory, having been decreed just five years earlier.

At Fictions of Emancipation: Carpeaux Recast at the Met. Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier.

Upon first viewing the work, many observers at the time hailed it as a strong statement against chattel slavery. In fact, abolitionists clamored for it. Multiples of the sculpture were cast in marble and bronze in varying sizes, and sold at a wide range of price points.

Over time, the sculpture became famous as a symbol of the evils of slavery. The Met curators note that replicas of Negress are still in production today, in materials as varied as wax (for candles) and resin.

a famous sculpture that has launched countless conversations

The enthusiastic initial response and ongoing popularity of Negress has made Carpeaux’s sculpture a focal point for conversations about a number of important topics. Including how Black women are portrayed in Western art. How imperialism and colonialism can be romanticized rather easily in artworks – and therefore dismissed as serious moral issues. And how fantasized images of the aftermath of slavery and captivity have shaped the views of people of all races about the actual experience of oppression.

Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier.

The Met’s curators – Elyse Nelson and Wendy S. Walters – provoke consideration of all these issues and more. They use the sculpture as a starting point to consider how the possession and objectification of Black bodies have long been the subject of fantasies and fetishes in Western art. Particularly in the aftermath of the emancipation of slaves in the British and French Caribbean colonies and in the U.S. And in the wake of the successful slave revolt in Haiti against the French.

The irony of portraying emancipation using an image of a bound and captive Black woman may have been lost on Carpeaux and his contemporaries. In fact, while the name of the actual model for the work has been lost to history, she was almost surely a free and independent Black woman. But her face has been immortalized as the visage of a pitiable captive.

Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux, Negresse,1868. Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier.

there were many works celebrating emancipation with images of degraded black slaves

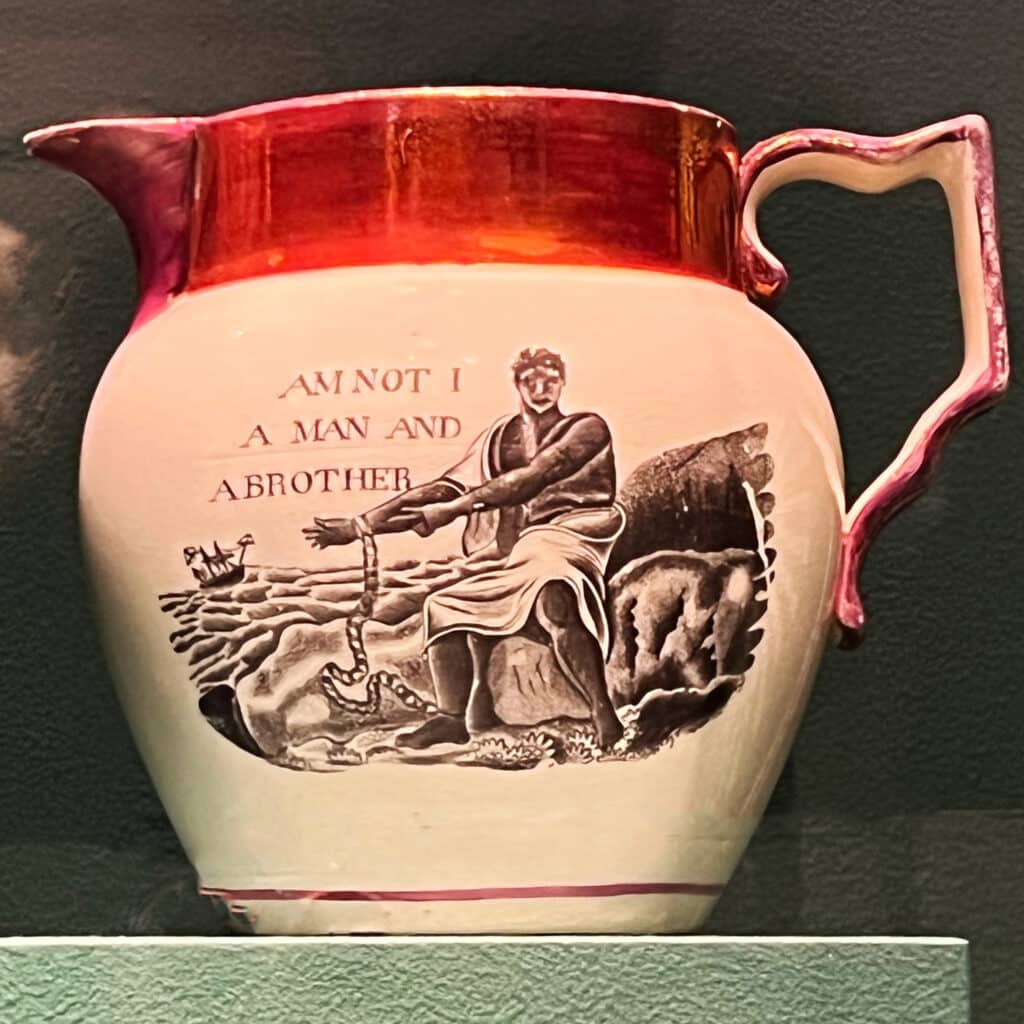

As anti-slavery sentiments spread across America and parts of Western Europe, artists and craftsmen began to create decorative objects featuring antislavery images.

The curators note that many of them featured pathetic Black figures: submissive, defeated and begging for their freedom. As with Negress, while these objects and artworks purported to celebrate emancipation, the images almost always portrayed Black men and women in captivity. Often complete with shackles, chains and thick ropes.

the wedgewood medallion

As early as 1787, the Wedgewood company issued a cameo medallion depicting a captive Black man. Its inscription was “Am I not a man and a brother?”

At Carpeaux Recast at the Met Museum, a famous sculpture is the basis for assessing Western art about slavery. Wedgewood collectible pitcher. Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier

This base image became a popular symbol of the antislavery movement in England, France and the U.S. The people buying and displaying these trinkets may have had pure intentions. But the underlying message of the image is clear when seen with modern eyes: blackness, subservience and slavery were all of a piece.

Boizot’s Porcelain Group

Even when the images in Western works of the era appear at first glance to portray freed slaves in a more positive and dignified light, closer examination reveals that the dehumanizing visual cues and codes are still present.

Louis Simon Boizot, Porcelain Group of a Free Man and Woman. Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier.

For example, in Porcelain Group of a Free Man and Woman, Louis Simon Boizot portrays a free Black couple holding symbols of equality associated with the French Revolution. But the inscription is rendered in broken ungrammatical French, implying that these subjects are deserving of a lesser kind of freedom than their white peers.

in this era, art objectifying people of color as “types” based on ethnography was common

To place Negress in historical context, the Met curators explain that while Carpeaux was working on Why Born Enslaved! he was also crafting a monumental decorative fountain sculpture called The Four Parts of the World Supporting the Celestial Globe.

The fountain – an homage to French imperialism – was a quintessential work of its time. Whether in sculpture, drawing or painting, men and women of color were used to personify specific ideas, people or regions of the world.

Their faces were used as stand-ins for whole races or continents of people. As the curators point out using several examples, certain ethnic “types” were widely recognized by viewers of all economic strata. And the place of these exotic people of color in the social hierarchy – versus those in the West – was clear.

these stereotypes extended not just to black people, but also to native Americans and those from Asia

For example, in a bust Carpeaux created as he was developing The Four Parts of the World, called The Chinese Man, the image of one man is meant to stand in for every inhabitant of the continent of Asia.

The Chinese Man, Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux. Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier.

In the work Allegory of Africa by Frederic-Auguste Bartholdi, a male figure is intended to personify the entire population of Africa.

Allegory of Africa, Frederic-Auguste Bartholdi. Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier.

Charles-Henri-Joseph Cordier sculpted Woman from the French Colonies in 1861. Its original title invoked a slur directed at mixed-race women. The classically-inspired drapery is respectful enough. But the heavy jewelry reflects the stereotype of the Black woman as an object of sexual desire. The images of Black women being rendered helpless and vulnerable – and in bondage – certainly seem to have been intended to fuel the fantasies of some of their creators.

Charles-Henri-Joseph Cordier, Woman from the French Colonies, 1861. Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier.

Ironically, the first work of this type sculpted by Collier was a male figure. Bust After Seid Enkess, 1848, portrayed a formerly enslaved Sudanese man as the ideal embodiment of Africa. It was seen as a celebration of Europe’s new enlightenment on the moral question of slavery. The work launched Cordier’s career as a master of ethnographic busts.

behold the African Venus

Perhaps the most famous of this genre is Cordier’s Bust of a Woman, 1851. It’s a fantasized portrait of a Black woman that later became known as African Venus. The name nods to the Greek goddess of love and beauty, but the woman depicted is highly sexualized.

Charles-Henri-Joseph Cordier, Bust After Seid Enkess,1848 (left). Charles-Henri-Joseph Cordier, Bust of a Woman, 1851 (right). Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier.

Smaller versions of busts and sculptures like these became highly popular as home décor in Europe, perhaps for some as form of virtue signaling. Even as colonialism and its concomitant brutalities continued to expand across the globe.

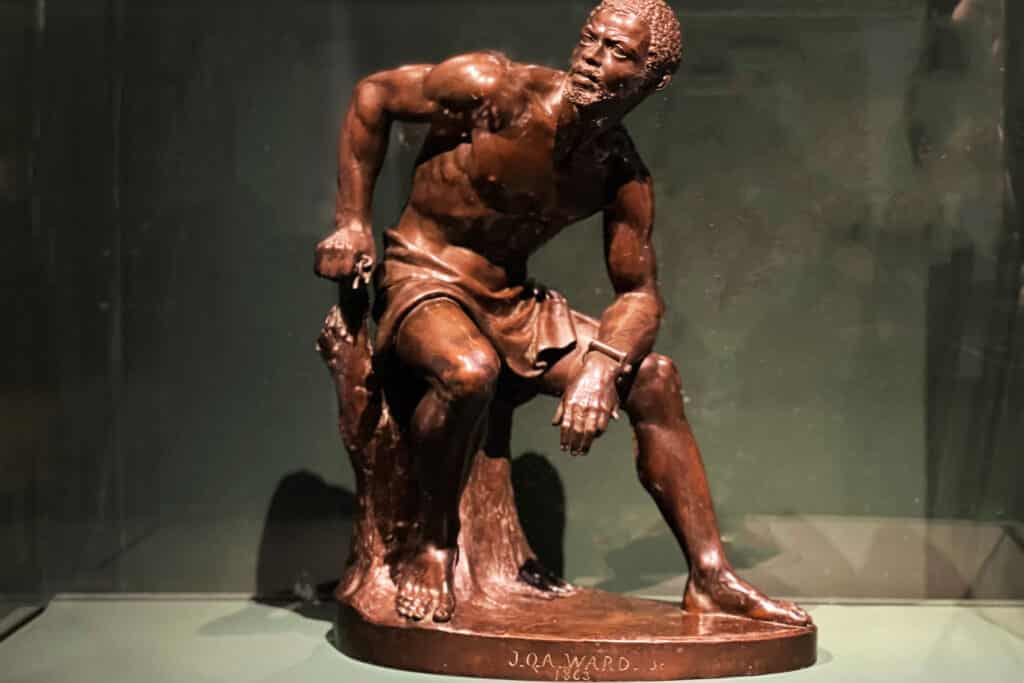

notable 19th century exceptions to demeaning portrayals

The exhibit is well-balanced, and we also learn of some notable exceptions to these practices. For example, a playing card created to celebrate the Haitian uprising that achieved freedom for the island’s population portrays a confident Black male figure surrounded by symbols of the French values of liberty and equality.

John Quincy Adams Ward, The Freedman. Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier.

An American sculptor, John Quincy Adams Ward, captured the optimism and trepidation of newly-freed slaves with his work “The Freedman.”

The male figure holds a broken chain in his fist. Yet the fact that he’s only partially clothed may signal his poverty. Tipping the scales to the positive, at least in the view of the curators, is that the male figure seems poised to stand. He seems to be on the verge of claiming agency, dignity and autonomy for himself.

emancipation in the work of one 19th-century black artist

Edmonia Lewis (1844-1907) was that rarest of people in her era: a Black woman sculptor. In Rome in 1867 – just two years after the Emancipation Proclamation in the U.S. – she unveiled her work “Forever Free.” The work is now part of the permanent collection of the Howard University Gallery of Art.

At Carpeaux Recast at the Met, a famous sculpture exposes the fantasies of Western artists about slavery and Emancipation. Edmonia Lewis, Forever Free, 1867. Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier.

In it, a free Black man stands with his fist raised. His other hand is on the shoulder of a woman who is kneeling and clasping her hands. The curators of the exhibit note that this may signify what Lewis imagined might be two diverging future paths for free Black people.

In a poignant footnote, we also learn that unlike other sculptors of her era, Lewis did most of her carving in front of an audience. She carved “Forever Free” in full view of others, because there was doubt as to whether or not she was actually the sculptor of her own work.

the modern response: enter Beyoncé, Kara and Kehinde

Pop culture probably first took notice of Carpeaux’s famous statue when it appeared in an ad campaign in 2020 for Beyoncé’s Adidas x Ivy Park collection.

At Carpeaux Recast at the Met, a famous sculpture exposes the fantasies of Western artists about slavery. Photo Credit: Harper’s Bazaar.

Beyoncé is standing amidst what appear to be Greek ruins. Carpeaux’s bust sits atop a pedestal next to her. On her other side sits a bust of a Nubian queen. It’s an assertion of – and celebration of – the power of Black women – with not a care or concern about the original intent of the work.

Even before this ad, many Black people chose to view Why Born Enslaved! as an emblem of Black beauty. And an homage to fierce Black women. And why not? Her hair is natural, she is beautiful, and she radiates intelligence, fortitude and strength. It may not have been what Carpeaux intended – but we all know that meaning is in the eye of the beholder.

Kehinde Wiley, after le Negress, 2006

For example, long before Beyonce’s ad campaign, Black contemporary artists took up Carpeaux’s sculpture and reimagined it. Kehinde Wiley famously created his bust – in a series of 250 – After Le Negress, 2006, as a riposte to the original.

An edition of Kehinde Wiley, After Le Negress, 2006 (right). Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier.

Made of marble dust and resin, Wiley reimagines Carpeaux’s figure as a male basketball player in an LA Lakers jersey. The image is in some ways a meditation on professional sports, and whether it is a form of slavery or liberation for Black men. The expression of doubt on the subject’s face leaves the matter clouded in ambiguity.

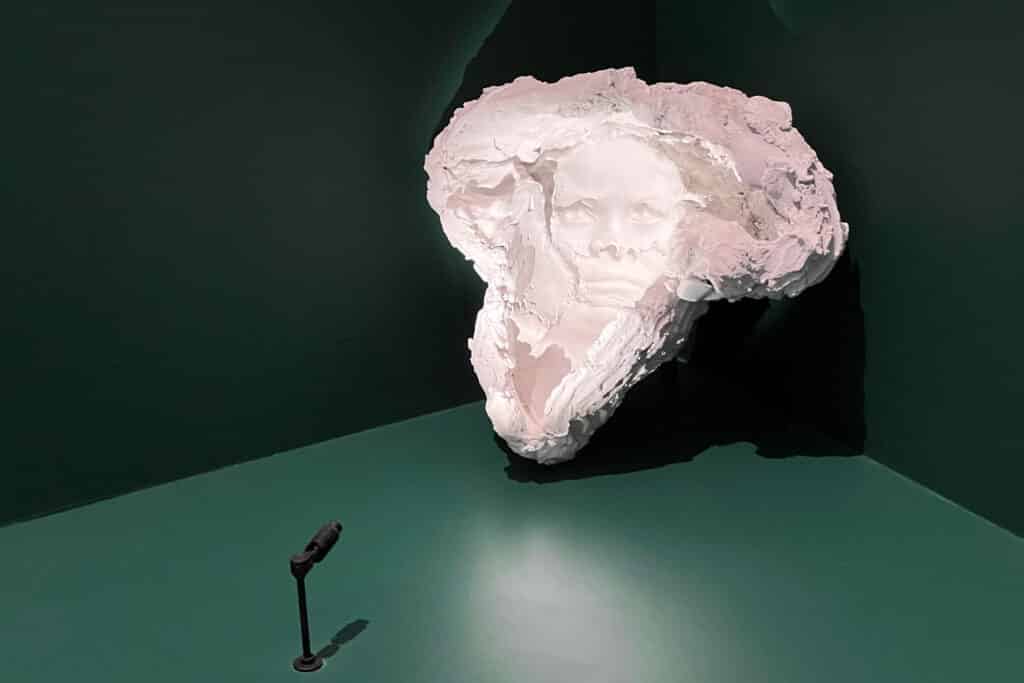

Kara Walker, Negress, 2017

In a stunning work, Kara Walker’s Negress, 2017, reimagines this work in wholly different way. The artist made an impression of the face directly from a reproduction of Carpeaux’s sculpture. Then she makes the resulting plaster mold into a powerful new visual. Walker essentially turns the bust inside out.

At Carpeaux Recast at the Met, a famous sculpture exposes the fantasies of Western artists about slavery. Kara Walker, Negress, 2017. Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier.

She designed the work to be displayed on the ground in a corner – as if it was nothing more than a discarded object. A single light creates ghostly shadows around the central image.

The curators note that it almost looks like an effigy. Walker has said of this piece, “I’m making work about fictions that have been handed down to me.”

museum visitors respond

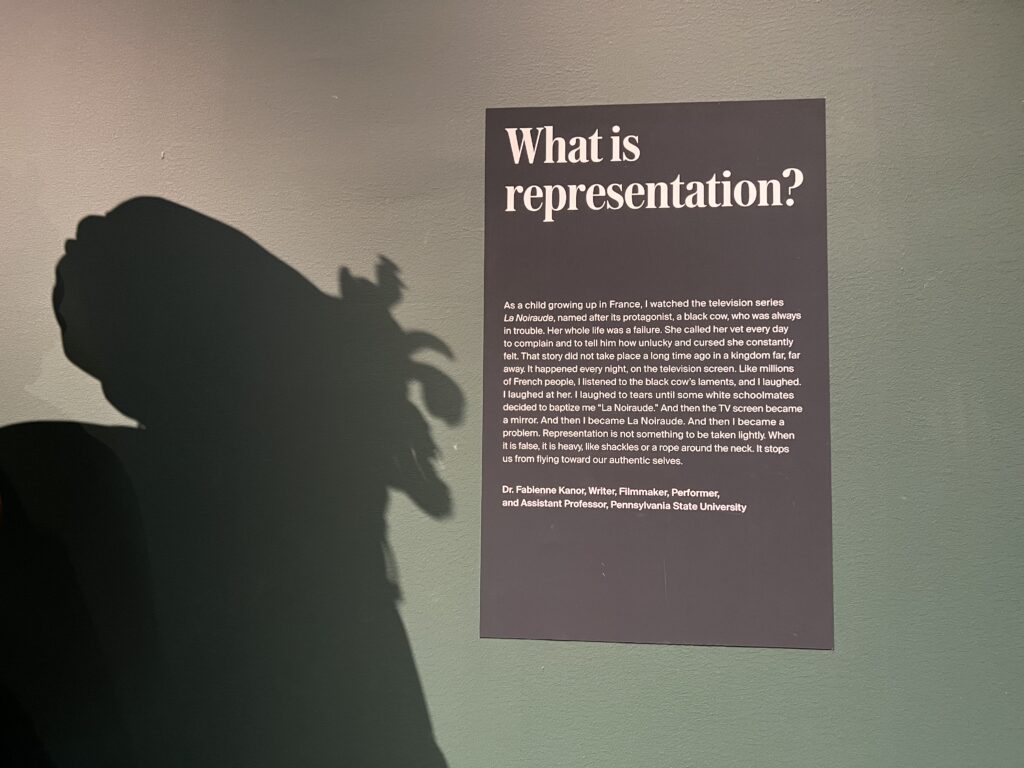

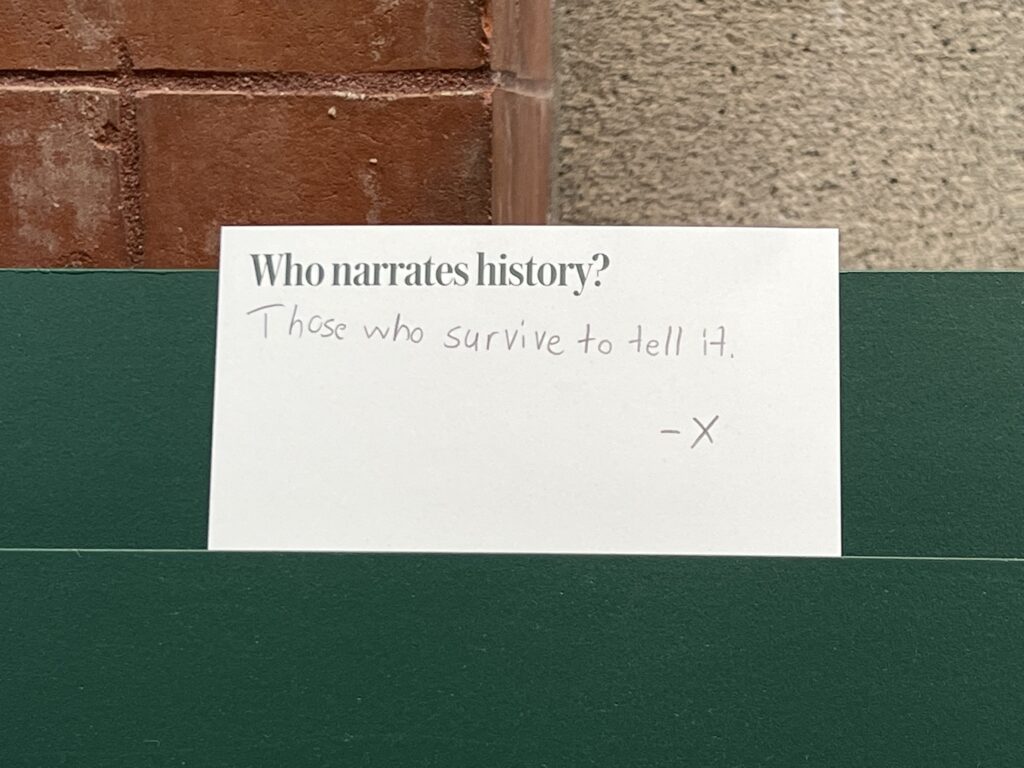

After viewing the exhibit, visitors are asked to share their responses to a number of questions. What is representation? Who narrates history? What is the legacy of the Black figure in Western art?

There were many eloquent and poignant responses, but this is the one that stayed with us.

At Carpeaux Recast at the Met, a famous sculpture exposes the fantasies of Western artists about slavery. Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier.

Emancipation Fantasies on view in One Famous Sculpture

At Fictions of Emancipation: Carpeaux Recast at the Met, a single famous sculpture exposes the fantasies of Western artists on the subjects of slavery and freedom. We hope you’ll catch this compact and powerfully moving exhibit for yourself. It will be at the museum until March 5, 2023.

join our community

For access to insider ideas and information on the world of luxury, sign up for our Dandelion Chandelier Newsletter here. And see luxury in a new light.

This article contains affiliate links to products independently selected by our editors. As an Amazon Associate and member of other affiliate programs, Dandelion Chandelier receives a commission for qualifying purchases made through these links.

Pamela Thomas-Graham is the Founder & CEO of Dandelion Chandelier. A Detroit native, she has 3 Harvard degrees and has written 3 mystery novels published by Simon & Schuster. After serving as a senior corporate executive, CEO of CNBC and partner at McKinsey, she now serves on the boards of several tech companies. She loves fashion, Paris, New York, books, contemporary art, running, skiing, coffee, Corgis and violets.